On Thursday, I took a visit to the Scroungers Center for Reusable Art Parts, aka SCRAP. Things got off to a great start when I spotted a pristine copy of Thacher Hurd’s Mama Don’t Allow in the free bin.

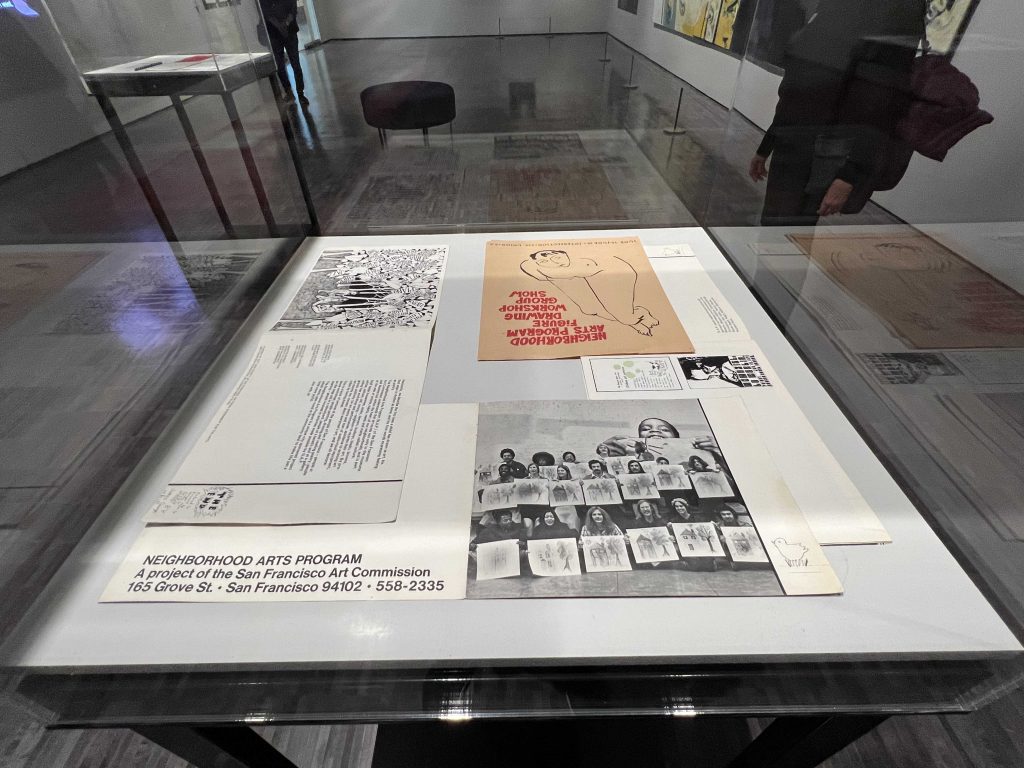

The Last Hoisan Poets & Del Sol Quartet have an upcoming tribute to artist Bernice Bing at the Asian Art Museum on April 20th. I have been wanting to learn more about Bing’s time working at SCRAP (1972-1976), ever since Lenore Chinn directed me to the Queer Cultural Center’s A Narrative Chronology, an timeline of Bernice Bing’s life by Moira Roth. Bing was a staff member of the Neighborhood Arts Program (under the auspices of the San Francisco Arts Commission), and she wrote grants to support the work of artists and in collaboration with others created the Scroungers Center for Reusable Art Parts (SCRAP), creating “junk” sculpture.

“Scrounging for Art’s Sake”, a 1977 article in the San Francisco Examiner, is included in the “Archives” table in “Into View: Bernice Bing” at the Asian Art Museum. In the black and white photo by Terry Schmitt, you can barely make out a smiling Bernice Bing, standing on the right before a jumble of free junk in the massive Pier 3 warehouse at Fort Mason.

In the article (page 332), Bing is quoted:

“I love the concept very much, said founding Scrap “scounger” Bernice Bing. “It’s ecologically very sound, and it’s giving a new, alternative, creative outlook to waste. We have so much waste in this country and if it could be transformed into something meaningful, it would really help the environment.”

Ironically, page 323 is a full page Macy’s shoe ad touting a two-tone open toe slide: “lifestride’s ‘bingo.‘ play it from any angle 26.00” There is also a mention of actor Victor Wong on page 325, “using a gold plaque commemorating a forgotten event as the backdrop of a wood-paper-cloth sculpture symbolically celebrating the long-suffering father of the average household.”

At SCRAP, we also discussed the evolution of the field of teaching artistry, and I was reminded of one glorious day in 2012 when we went to UC Berkeley for “Reaching for the Stars: A Forum on Music Education,” a conversation with conductor Gustavo Dudamel and José Antonio Abreu, founder of El Sistema, led by then Cal Performances director Matías Tarnopolsky.

At the open rehearsal with the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, conducted by Dudamel, the University Chorus of UC Berkeley and the Pacific Boychoir – the sheer numbers of bodies working together on stage was simply awe-inspiring.

Program notes for Cal Performances, Friday, November 30, 2012, 8pm Zellerbach Hall

Along with photos and video of the day, I saved an 2010 essay by Eric Booth, El System’s Open Secrets. In writing about El Sistema, Booth notes that “the energy of experimentation and aspiration is so palpable that El Sistema feels more like an inquiry than an institution.”

This spirit of exploration appears in everything they do. The frequency of

Eric Booth, El Sistema’s Open Secrets, May 2010.

performing takes it off the occasional-destination pedestal, narrowing the gap

between rehearsal and performance and making them both a healthy part of the larger exploration of striving for excellence. The frequency of students attending performances of other ensembles, both more and less experienced than their own, places their work in a greater continuum. Indeed, they hear other ensembles perform the same pieces they perform, so they feel themselves as part of a growing process and not as a competitive entity. I have described this elsewhere as the proleptic curriculum—the same pieces and practices revisited again and again over the years, accruing greater meaning each time, and providing opportunities for deep self-assessment of growth and satisfaction in success. The proleptic curriculum is a practice that serves inquiry in a deeply effective way.

“Tocar y luchar—to play and to fight” is a motto associated with El Sistema. When José Antonio Abreu accepted the 2009 TED Prize, Abreu shared, “Mother Teresa of Calcutta insisted on something that always impressed me: The most miserable and tragic thing about poverty is not the lack of bread or roof, but the feeling of being no-one — the feeling of not being anyone, the lack of identification, the lack of public esteem.” His wish for the world was to create a training program for 50 gifted musicians dedicated to bringing El Sistema to the United States.

When Abreu passed away on Saturday, March 24, 2018 at the age of 78, Gustavo Dudamel wrote, “Maestro José Antonio Abreu taught us that art is a universal right, and that inspiration and beauty irreversibly transform the soul of a child, making them a better, healthier and happier human being, and in turn, a better citizen. My commitment to Maestro Abreu and El Sistema is a commitment to the future, to those children who have not yet discovered music and art. To these children, and to the millions touched by Maestro Abreu’s legacy, I would like to say that this is just the beginning of the journey. We will continue to play music, sing and fight for the world that Maestro Abreu dreamed of.”

Callan las cuerdas.

Jorge Luis Borges, “Diecisiete haikus.” 1981.

La música sabía

lo que yo siento.

Meanwhile, at the Asian Art Museum, the art and ideas of Bernice Bing are slowly coming “Into View,” as Stanford University continues to digitize her archives for future study by art historians.

Lydia Matthews’ essay, “Quantum Bingo,” written for the Bernice Bing, Memorial Tribute and Retrospective at SomArts in 1999, closes with an artist statement written by Bing for her 1992 Triton Museum Exhibition.

Bernice Bing’s musing is equal parts inquiry and aspiration.

“What is the mystery? The mystery is the work in process. Visually, I sense a great order of things and attempt to transpose this mystery into a picture. I used to look for meaningful order in life, now I am accepting things as IS. That nothing is certain, and in my imagery is ever-changing. We are at an epoch of a brave new world, and my hope is that our views will change about how we see our world, not to stay with the things familiar, but to reach out for the unknown.“